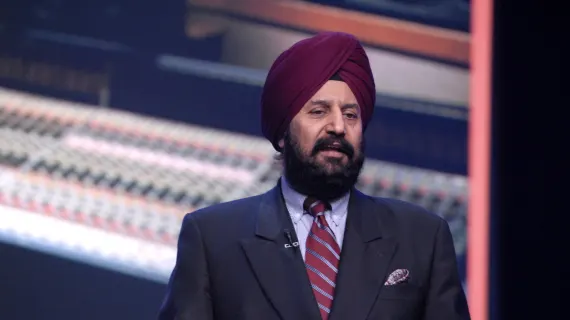

To people of a certain age in Silicon Valley, (i.e. elders), Satjiv Chahil, 72, is a familiar and recognized figure. That he is less known to younger techies is both unfortunate and telling.

Once you meet Chahil, you won’t forget him. He’s the charming, Indian-born American guy wearing a brightly colored turban — often with a matching blazer. Chahil loves documenting all the people he’s met (I think he invented the selfie, decades ago) and has a picture with everybody. One of my favorites is with Brazilian mega-novelist Paulo Coelho and German metal(ish) band Scorpions. (What?)

Much more than that though, the Zelig-like Chahil has been a mission-critical marketing executive at the biggest tech’s biggest companies — think Apple, IBM, HP and Xerox—at some of their most critical moments.

Even that is selling him short though. A “global intercultural and interdisciplinary innovator,” as he’s been described, is probably closer. He’s also exactly what’s missing from Silicon Valley right now. Unlike the modus operandi of today’s technocrats, Chahil’s life’s work has been to make technology essential to the creative, moral, and fun-loving continuum of human existence.

Apple in its heyday exemplified some of this thinking, and it’s no coincidence Chahil worked there for nine years. The company was a home to many out-of-the box, non-technical minds like Regis McKenna and Lee Clow, designers Hartmut Esslinger and Jony Ive — and, you could argue, Steve Jobs himself.

“My first experience in Silicon Valley was in the early 80s when I moved there from the east coast,” Chahil recalls. “The mindset was so different. It was welcoming to people from all over the world and all fields of interest. It was long-haired, music-loving scientists who wanted to make the world a better place. Now it’s people wanting to get rich quickly and manipulate the world.”

Please forgive the indulgence in good-old-days-ism, but it bears re-hearing because very little in American business or society is as important as Silicon Valley’s shifted priorities, aka, moral collapse. We’ll get into that some more, but first back to our protagonist.

Chahil, born to a well-off family in Amritsar, came to the U.S. for graduate school, receiving a degree in international management from the Thunderbird School at Arizona State in 1976. (Chahil just gave the fall convocation speech there this past Tuesday.) Then he began his career at IBM.

Discipline from IBM, creativity — and what not to do — from Xerox, and branding from Apple

“Silicon Valley was about changing the world. IBM world was about controlling the world. When I joined IBM, it could stand up to governments. Getting a job at IBM for me came from heaven,” Chahil says. “I wrote to my grandma in India, ‘your prayers have been answered.'”

In some ways, the company felt familiar.

“IBM was a very disciplined organization,” Chahil continues. “It felt like being in my British military boarding school again. The good aspects were that we were given training on ethics. We were not allowed to even expense a drink on our expense account. We were told to answer our mail as it came. But the whole company was driven by information, productivity and reporting controls. The business purpose was so different from where I landed up.”

Which was Silicon Valley. Chahil moved to another iconic, though radically different tech destination, Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center). Scientists there famously developed all manner of technology (graphic user interface, the mouse, desktop publishing), which Xerox never put to market but was later adopted, borrowed or stolen (some say) by the likes of Apple, Microsoft, Adobe and others.

“Xerox collected the most brilliant scientists and asked them to think of a paperless future,” he says. “Steve Jobs visited Xerox PARC [in 1979]. And he got what Xerox could not get. Macintosh and what Apple became, originated at Xerox PARC. Jobs hired away Larry Tesler, who was the creator of cut and paste [and also showed PARC’s tech to Jobs]. Larry became the chief scientist of Apple.

“One of my office neighbors was one of these long-haired genius scientists, Joe Becker. He figured out how to do foreign languages on computers and was the father of Unicode, which allows not just languages, but all those emojis on your computer. I suggested ‘why don’t we launch multilingual desktop computing?’”

But Xerox passed and “one after the other, all the people left Xerox.” Chahil joined the exodus.

“I was not interested in going to Apple because I thought they just knocked off Xerox technology,” he says. “But a person presented me with a job spec that was my proposal to Xerox of what we should be doing. Apple, then under John Scully, had created a new division called Apple Pacific, and they were looking for a marketing leader.”

Chahil says Scully thought it was critical for Apple to succeed in Japan. “We ended up becoming the most desired brand in Japan and the first success story of an American company. Steve [Jobs] [also] had a great admiration for Sony and being in Japan. I was the liaison with Sony.”

Though Chahil never worked directly with Jobs, “I think he was the greatest communicator there was. I crossed paths with him on various occasions. I learned a lot from him indirectly, because I admired how he marketed his quest for perfection. Steve Jobs never shared where his learnings came from. I sought out who he learned from [like] Regis McKenna, the founder of the Silicon Valley way of marketing, through connections with influences and ecosystems, [and] Hartmut Esslinger who taught Steve Jobs design, designing the first Mac.”

Applying the lessons from Apple to HP

Chahil later went to work for HP, where he applied it all.

“The expert opinion was that no American company could survive [in the PC] business. HP had [a] dilemma: Should they drop the PC business, or keep [it as] it was important for their scale and for selling printers? If they keep it, they must make it profit neutral. I was asked if I would join the team and help revive this business.

“I spoke with Paul Saffo, from the Institute for the Future. And he said to me ‘HP is not a job. It’s a cause.’ I said, ‘Why is it a cause for me?’ And he says, ‘because the whole mindset of Silicon Valley was driven by Hewlett and Packard, the open door policy, the respect for the environment. You can’t let this company sink.’

“In those days they used to say ‘if HP were marketing sushi, they’d call it cold dead fish.’ The challenge was how to take that mentality and bring some of the Apple way of thinking and pizzazz and cachet. Fortunately, they gave me the latitude to make massive changes.

“We came up with the idea of ‘let’s make the computer personal again.’ We also turned celebrity marketing sideways. We decided we’d celebrate people from sports, music, film, and fashion and show their life and support their causes. We never showed their faces. We showed who they were about. And then we would donate. The first one we did was with Jay Z. Similarly, with Serena Williams, Petra Nemcova and others.

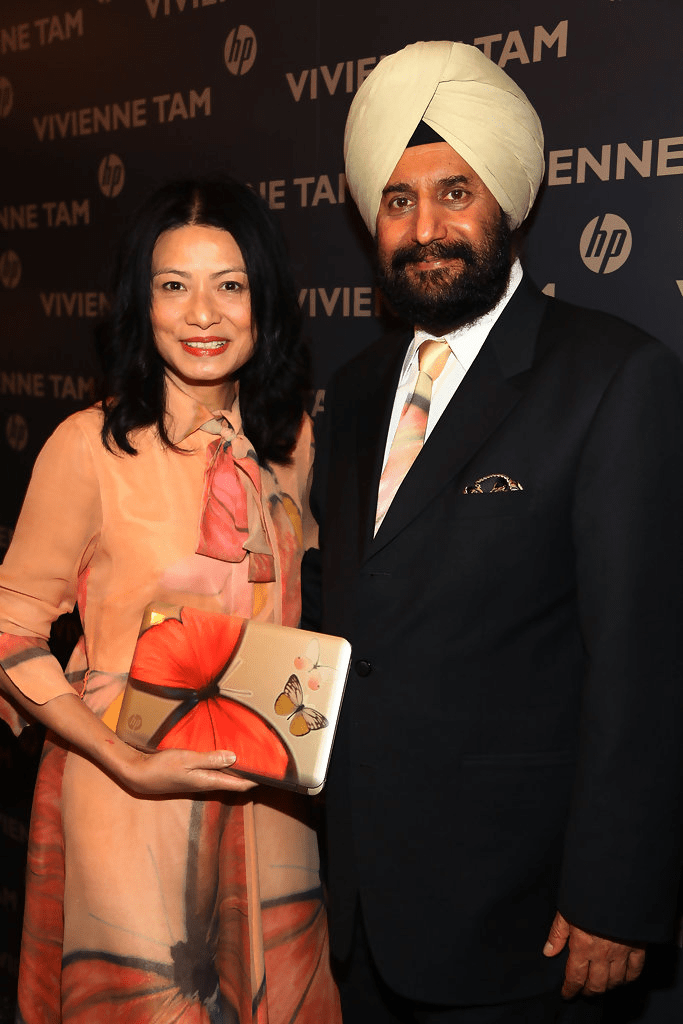

Chahil says he also was looking for a fashion designer who was “global, whose designs were timeless, who had a real passion for materials. That’s how we discovered Vivienne [Tam.] We had a meeting with her and we were wondering about the product and she said, ‘it should be like a clutch.’ All of us were thinking of the automobile clutch. We discovered the computer industry always treated women as an afterthought.” Chahill got the Vivienne Tam tablet made and it sold out in three months.

Overall, Chahil says these campaigns made HP’s PC business number one in market share and profitability.

Finally, I ask Chahil if he is sanguine about Silicon Valley going forward.

“With IBM, the regulators were watching like a hawk,” he says. “Facebook just took off, buying Instagram, WhatsApp, so they got the world from all sides. And Amazon has ended up with monopolistic powers and behaviors. This needs to be challenged. Consumers need to push back.

“I think the moral compass will come back. I’m glad that people are putting pressure on. There have been management changes at Uber and other places. I’m hoping new companies would emerge and the big ones would also correct their culture and practices.

There’s a whole class of elders out there, like Chahill, McKenna, Becker, Esslinger, Saffo (Tesler passed away in 2020), along with Stewart Brand, John Warnock and hundreds of others, ignored by today’s Silicon Valley billionaire class, who display little of that group’s worldliness, holistic sensibility and ethics.

Tracking down these tech forebearers, sounding them out and learning from them might go a long way to fixing that broken compass.