The name of a boy found dead inside a cardboard container in 1957 in Fox Chase – perhaps Philadelphia’s most enduring mystery – was revealed Thursday.

Nearly 66 years after the battered body of a young boy was found stuffed inside a cardboard box, Philadelphia police say they have finally unlocked a central mystery in the city’s most notorious cold case: The victim’s identity.

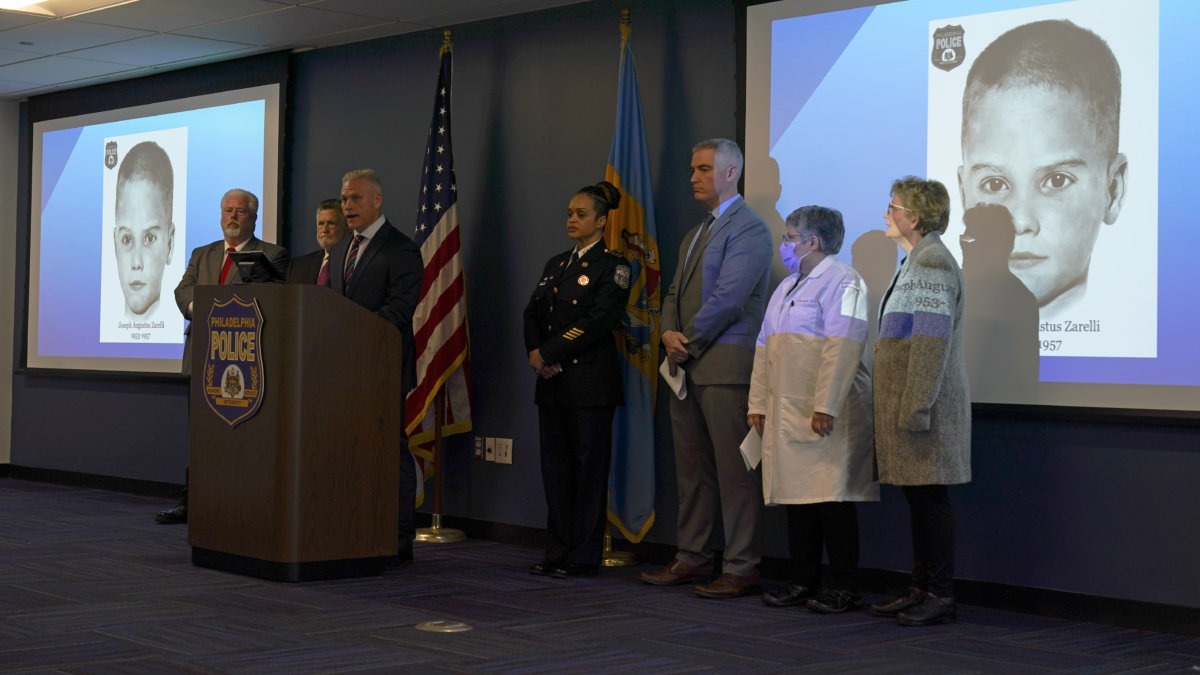

Investigators used DNA evidence and genealogical research to identify the “Boy in the Box” as Joseph Augustus Zarelli, a 4-year-old from West Philadelphia.

The city’s oldest unsolved homicide has “haunted this community, the Philadelphia police department, our nation, and the world,” Philadelphia Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw said at a news conference.

“When people think about the boy in the box, a profound sadness his felt, not just because a child was murdered, but because his entire identity and his rightful claim to own his existence was taken away,” she said.

Police say detective work and DNA analysis helped them finally learn Joseph’s name. The homicide investigation remains open, and authorities said they hoped releasing Joseph’s name would spur a fresh round of leads.

Police said both of Joseph’s parents are dead, but he has living relatives.

“We have our suspicions as to who may be responsible, but it would be irresponsible of me to share these suspicions as this remains an active and ongoing criminal investigation,” Philadelphia Police Homicide Captain Jason Smith said Thursday.

Smith said the PPD would not identify the parents – both of whom are deceased – out of respect for Joseph’s multiple living siblings.

Joseph lived in the area of 61st and Market streets and was never reported missing, Smith said. He added that detectives hope Thursday’s announcement will generate “an avalanche of tips from the public.”

The child’s naked, badly bruised body was found on Feb. 25, 1957, in a wooded area of Philadelphia’s Fox Chase neighborhood. The boy, who was 4 years old, had been wrapped in a blanket and placed inside a large JCPenney bassinet box. Police say he was malnourished. He’d been beaten to death.

The boy’s photo was put on a poster and plastered all over the city as police worked to identify him and catch his killer.

Detectives pursued and discarded hundreds of leads — that he was a Hungarian refugee, a boy who’d been kidnapped outside a Long Island supermarket in 1955, a variety of other missing children. They investigated a pair of traveling carnival workers and a family who operated a nearby foster home, but ruled them out as suspects.

An Ohio woman claimed her mother bought the boy from his birth parents in 1954, kept him in the basement of their suburban Philadelphia home, and killed him in a fit of rage. Authorities found her credible but couldn’t corroborate her story — another dead end.

“I’m hopeful that there’s somebody who is in their mid-to-late 70s, possibly 80s who remembers that child,” Smith told reporters after acknowledging that police may never arrest or even identify Joseph’s killer.

Jack Tomczuk

His body was discovered bruised and wrapped in a blanket on a February morning more than 65 years ago in a wooded area near the corner of Susquehanna and Verree roads.

In an attempt to identify the boy, who was also referred to as America’s Unknown Child, fliers were mailed to city residents alongside their gas bills. Investigators created a death mask and dressed his body for a post-mortem photo.

Joseph was initially buried in an unmarked grave in the Far Northeast before his remains were exhumed in 1998 to search for DNA evidence. That effort did not lead to a break in the case, and he was reburied at Ivy Hill Cemetery in Cedarbrook.

Three years ago, Joseph’s body was exhumed again, and detectives worked with forensic genealogists to locate family members.

“This was the most challenging case of my whole career,” said Colleen Fitzpatrick, of Identifinders International, a firm that worked on the investigation. “It took two-and-a-half years to get the DNA in shape.”

Eventually, authorities made contact with relatives on Joseph’s mother’s side and were able to identify his biological mother. A birth certificate listed his father, whose parentage was later confirmed by DNA testing, Smith said.

Ryan Gallagher, manager of the PPD’s forensics lab, said Joseph’s case was the first identification made as part of a new forensic genealogy program.

Detectives and genealogists are in the process of using the techniques to identify human remains in more than a dozen other local cases, according to Smith.