KYIV — Recent satellite images of Russian-occupied Crimea obtained by RFE/RL show airfields, air-defense sites, and ships that defense experts say could rank as prime targets for the Ukrainian military as it seeks to weaken Moscow’s forces and recapture territory they have seized.

The significance of Crimea as a launching pad for Russian strikes on mainland Ukraine has increased following the retreat of Russian forces a month ago from the city of Kherson — the only regional capital they had captured since Moscow launched a large-scale invasion in February — and the eastern bank of the Dnieper River in the surrounding area.

Russian forces have suffered numerous setbacks since the invasion but continue to hold parts of the Kherson, Zaporizhzhya, Luhansk, and Donetsk regions in addition to Crimea, which they occupied in 2014. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has repeatedly said Kyiv’s goal is to regain control over the entire country, including Crimea.

Journalists from RFE/RL’s Crimea.Realities have created a database that identifies more than 150 Russian military sites on the peninsula. Along with defense analysts and colleagues from Schemes, the investigative unit of RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service, they reviewed fresh footage from the U.S. satellite imagery company Planet Labs depicting the most important facilities.

Here is what they found.

Aviation

Out of the 10 active military airfields on Crimea, the satellite images suggest that, as of mid-November, the airfield at Dzhankoy had become Russia’s main logistics hub for its operations in southern Ukraine. It also serves as a base for its attack helicopters.

Dzhankoy now ranks “No. 1 in [the] top five” targets for Ukrainian strikes, said Viktor Kevlyuk, a defense industry expert at the Center for Defense Strategies, a Kyiv think tank.

A former commander of the Ukrainian Navy, Vice Admiral Ihor Voronchenko, termed Dzhankoy a “very excellent base” for Russian ground and air forces since it “expands the radius of action — primarily of army aviation” in southern Ukraine.

Russia’s use of its runway is now “quite intensive,” said Kevlyuk, since the airstrip can handle heavy planes ferrying troops into the nearby Kherson and Zaporizhzhya regions to the north, where Russian forces control substantial amount of land east and south of the Dnieper. “It’s worth watching.”

Planet Labs images from October 31 show over 50 helicopters stationed at the Dzhankoy airfield. Among them are the Ka-52, an attack helicopter capable of destroying tanks and performing aerial reconnaissance; the Mi-28 combat helicopter, billed by Rosoboroneksport, Russia’s state-run military hardware export agency, as a “flying tank”; the Mi-35 combat helicopter; and the Mi-8 helicopter, a multitasker used for transport, attacks and reconnaissance.

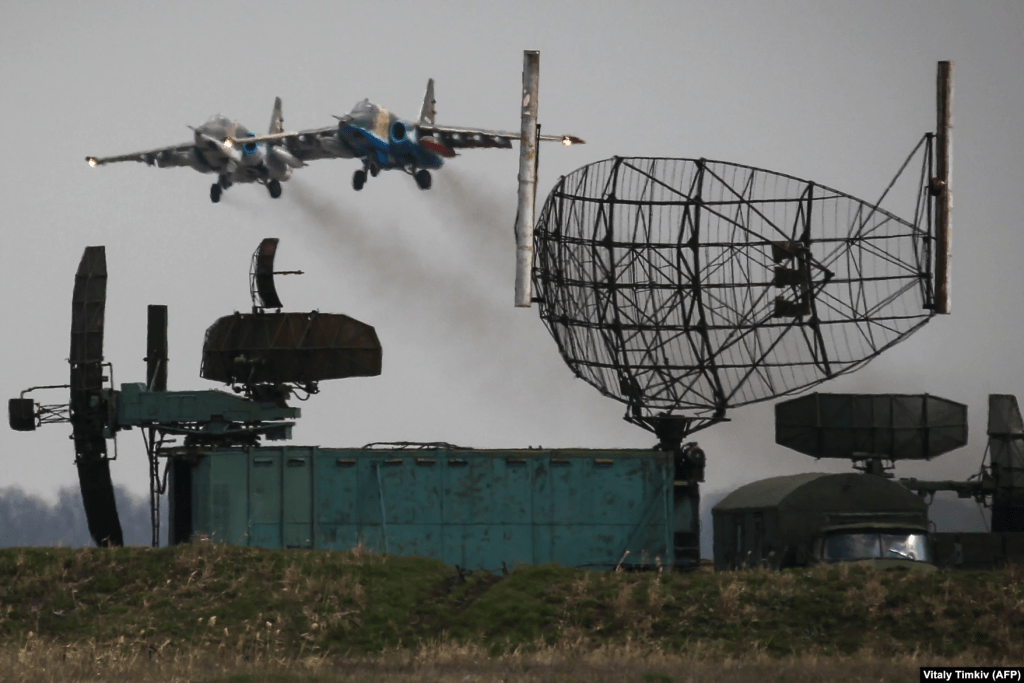

Aside from helicopters, cargo planes and Su-25 attack aircraft often fly into Dzhankoy, the Planet Labs images show. The airfield appears to have at least three warehouses with ammunition, and equipped locations for antiaircraft missile systems.

Striking the Dzhankoy airfield would further complicate Russian troops’ logistical problems in southern Ukraine and would “be very effective, timely, and generally useful” for Ukrainian forces in the Kherson region, Kevlyuk said.

Two other airfields also attracted analysts’ attention.

Aircraft from Hvardiyske, about 22 kilometers north of Crimea’s capital, Simferopol, supply the Su-25 fighter planes and Su-24 bombers Russia most often uses in its short-range air strikes on Ukrainian-controlled territory. A factory at western Crimea’s coastal town of Yevpatoria repairs the Su-25s, according to analysts.

This airfield also houses a regiment that is one of the Russian military’s main air groups.

To the southwest, Planet Labs images from November 15 show Sukhoi Su-27, Su-34, and MiG-31 fighter jets stationed at the Belbek airfield, just east of the Crimean port city of Sevastopol, home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. The fighter jets appear to make up the majority of the aircraft there.

In 2018, Russia intended Belbek to be used for strategic bombers, but satellite images show none of these now — most likely because stationing the bombers at Russia’s Engels or Shaikovka air bases is safer than risking their destruction by a drone or missile in Crimea, says Denys Tomenchuk, the editor of the aviation news site MilitaryAviation.in.UA.

Since August, explosions and fires have occurred at all three of those facilities.

Navy

Russia launches most of its Kalibr cruise missiles at Ukrainian population centers from the Black Sea waters off the Crimean Peninsula. On December 5, Zelenskiy vowed that Kyiv would work to ensure that those missiles “can only be at the bottom” of the sea.

A November 9 Planet Lab image shows the Projects 1239 and 1241 ships that launch these cruise missiles docked near Holland Bay, a few kilometers outside Sevastopol, home to Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

These ships typically go out into the Black Sea “a very short distance” and fire their missiles from there in order to avoid the risk of a rocket hitting one of Sevastopol’s mountain slopes, a former deputy chief of the Ukrainian Navy, Andriy Ryzhenko, commented to RFE/RL’s Crimea.Realities.

The Kalibr cruise missiles’ off-board storage sites are not known, but Voronchenko, who oversaw the Ukrainian Navy from 2016 to 2020, conjectures that they could be kept in the Inkerman mountain tunnels in southwestern Crimea. Ukraine formerly used the location to store torpedoes, mines, and ammunition for ship crews, he said.

“These tunnels are very securely covered,” Voronchenko told Crimea.Realities, which is also a unit of RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service. “It will take a lot of effort to hit these formations.”

Aside from the Kalibr missile ships (Projects 1239 and 1241), the image above shows large amphibious ships (Projects 1135, 1171, 775), patrol ships (Project 22160) and a Project 11356 cruiser that is either the Black Sea fleet’s disabled flagship, Admiral Makarov, or fellow frigate Admiral Essen.

A lack of space means that these ships were docked side by side in Sevastopol. An apparent patrol ship — likely operating an underwater monitoring device with a radius of 1 kilometer, according to Ryzhenko — remained around the clock in the center of the bay.

Anti-Missile, Antiaircraft Networks

Attacking these targets in Crimea, however, could pose a challenge, military experts say. When Russian forces annexed the peninsula in 2014, they also gained control of its S-300 and Buk antiaircraft defense network. Russia has since added S-400 antiaircraft systems and the Bal and Bastion coastal missile systems.

The Planet Lab images show six Bastion-P mobile missile launchers in a lot near Feodosia, a regional town not far from the strategic Kerch Strait, site of the Russian-built bridge linking Crimea with Russia that was badly damaged by an explosion that Moscow blamed on Ukraine.

Kevlyuk said, however, that the site was a military camp, rather than “a place from where they shoot.”

Additional satellite images show the Bastion systems on southern Crimea’s mountain slopes.

Experts believe that ammunition for these antiaircraft-missile and coastal complexes is most likely stored in the western Crimean coastal town of Chornomorske.