A University of Alberta analysis has identified two new minerals in a 4.5-billion-year-old space rock found in Somalia.

A third new mineral was identified by an American researcher and officially approved on Monday.

The 15-tonne meteorite was found by prospectors searching for opal two years ago in a lush valley where camels forage.

Canadian scientists have identified two new minerals never seen before in nature — and they came to our planet inside a 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite.

New minerals: Minerals are solid elements or compounds with orderly internal structures, and they come in many forms — to date, we’ve discovered more than 5,000 minerals on Earth, including calcite, diamond, and quartz, and even a handful of unique minerals on the moon.

The researchers have named the new minerals “elaliite” and “elkinstantonite,” after the meteorite itself and Lindy Elkins-Tanton, vice president of the Arizona State University Interplanetary Initiative, respectively.

“Lindy has done a lot of work on how the cores of planets form, how these iron nickel cores form, and the closest analogue we have are iron meteorites,” said U of A geologist Chris Herd, “so it made sense to name a mineral after her and recognize her contributions to science.”

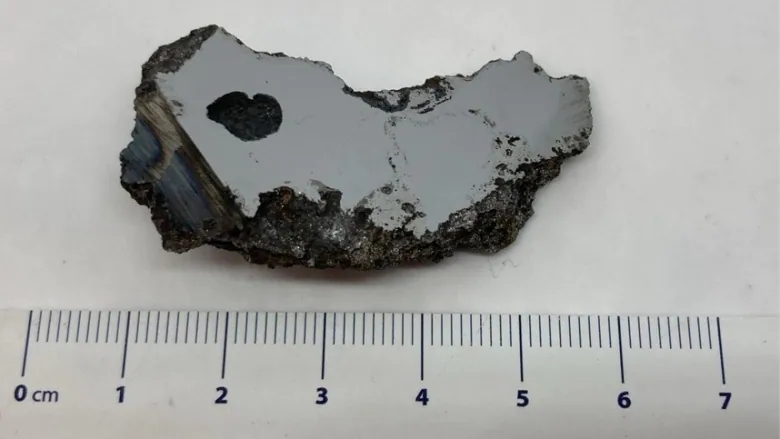

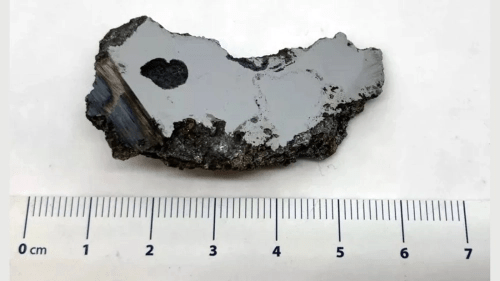

The discovery: Herd was analyzing a 70-gram slice of El Ali in an attempt to classify the meteorite (spoiler: it’s an “iron, IAB complex” meteorite) when he saw signs of entirely new minerals.

He brought the sample to Andrew Locock, head of the U of A’s Electron Microprobe Laboratory, who was able to match the composition of the new minerals to ones that had been created synthetically before but never discovered in nature.

The researchers have already spotted signs of a third new mineral in their sample and believe that they might discover even more if more of the huge meteorite is analyzed.

Local herders were aware of the rock for more than five generations, according to its profile with the International Society for Meteoritics and Planetary Science. It had been used as an anvil to sharpen knives and was memorialized in folklore, songs, dances, and poems.

About 70 grams were sent to the University of Alberta’s earth and atmospheric sciences department, where it came under the purview of Chris Herd.

“What happened was during the process of classifying it, when I was looking at the slides that we had on an electron microscope, I saw some minerals that it couldn’t really identify,” said Herd, a professor and curator of the university’s meteorite collection, in an interview.

Earlier this year, the head of the university’s electron microprobe laboratory, Andrew Locock, examined and identified two new minerals. The task was made easier by the fact that the compositions had been synthesized previously in France in the 1980s.

“On the first day that he did some analysis, he told me that we had at least two new minerals inside of this meteorite,” Herd said.

“You don’t typically come across the minerals in sort of routine analysis like this. And so it was really exciting.”

Although the crystal structure had been created in a lab previously, only once it’s discovered in nature are they called minerals and named. The two new minerals have been named elaliite and elkinstantonite.

The first takes its name from the meteorite itself, called “Eli Ali” after the town near where it was found. Herd named the second after planetary scientist Lindy Elkins-Tanton because of her work exploring how planet cores are formed.

The research is being done in collaboration with UCLA and the California Institute of Technology. Herd said Chi Ma, a mineralogist at the institute, has just gone through the approval process to declare a third new mineral.

Olsenite is named after Edward J. Olsen, the former mineralogy and meteorites curator at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago who helped described several new minerals from meteorites.

“I just feel really fortunate to be involved in it,” Herd said.

“Because most people in the earth and planetary sciences don’t ever get a chance to describe one new mineral, let alone more than one.”

The meteorite has been classified as Iron, IAB, one of 350 in that category. It is the ninth-largest meteorite ever found.

Herd presented the findings at the Space Exploration Symposium in November.

Chris Herd is the curator of the University of Alberta’s meteorite collection, which houses 350 specimens from around the world. (Submitted by Chris Herd)

Kim Tait, senior curator of mineralogy at the Royal Ontario Museum, said although finding new minerals in meteorites is not common, they are a great place to look.

“Because these rocks have undergone shock events and high pressures and temperatures and different conditions that we would see here on Earth,” she said, adding that despite the many combinations of the periodic table there are only 5,851 minerals known to humanity.

The meteorite can lead to a better understanding of how such objects are formed. Tait also notes that an iron meteorite would come from the core of a planet that no longer exists.

“We don’t get a lot of chances, obviously — no chances — to sample our own core on our planet,” she said.

“So having the opportunity to look at iron meteorites is very special in a lot of ways”

Herd said new mineral discoveries can yield new uses in the future.

“We’re working with someone in chemistry here to synthesize these minerals to explore them a bit more,” he said. “You never know.”

The future of the meteorite itself is uncertain, however. The Somali government confiscated the rock before then releasing it to miners.

Herd said it has been exported to China, where it is awaiting purchase.